It is an unfortunate fact that many martial artists suffer from knee pain. In this article, we will discuss a common source of knee pain common to practitioners of karate and other martial arts. We explain conditions that create and exacerbate such pain, how to identify those conditions, and how to remedy them.

Knee Pain and Joint Alignment

Joint pain can be very frustrating. Many suffering martial artists want to train, but chronic knee pain holds them back.

If your knees hurt during or after training, there is a good chance you may be exacerbating the condition by placing your knees in improper alignment. Martial artists of all experiences can fall into patterns of movement that are unhealthy for their joints. Repeating such movements can lead to injury over time.

There are two items of good news. First, movement patterns can be improved. Second, improved movement patters not only help prevent injury, they also increase your striking power and fighting abilities.

The knee is often the body joint that starts hurting first. This is because the knee joint is located in between two very mobile joints: the hip (above), and the ankle (below). Let’s look at our anatomy and understand what “joint alignment” truly means.

Acknowledgment:

Special thanks to Stanford sports medicine doctor and karateka Michael Fredericson, M.D. for his review and input.

A Little Anatomy

The hip is one of the most mobile joints in the human body. It is a ball-and-socket joint. The hip is capable of motion in three planes – flexion and extension (forward/back); abduction and adduction (side movement), and internal rotation and external rotation (turning toward, or away, from the body).

The ankle joint along with the foot also allow for a high degree of mobility. Our ankles can flex (dorsiflexion) and extend (planar flexion), as well as rotate in two directions (inversion/eversion). Our feet can pronate (turn inward) and supinate (turn outward).

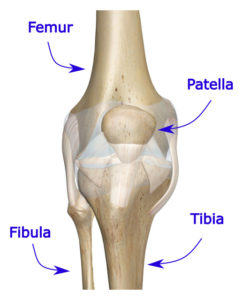

In between the highly mobile hip and the highly mobile ankle/foot is the knee joint. The knee joint is a hinge joint, and it is predominantly designed to flex and extend. Although the knee (really, the tibia) is capable of some rotation, rotation is not what the knee prefers. The knee is able to bear the highest loads, and function in the most optimal way when it is in straight alignment. By straight alignment, I mean that that the knee is in the same geometrical plane as the corresponding hip and foot. Another way to think about straight alignment is by observing that the kneecap is pointing in the direction of the toes.

As we will see, a common problem occurs when martial artists don’t properly rotate their hip joints. This requires the knee to participate in excessive amounts of rotational movement. Over time, this leads to wear and tear, and results in knee pain. If we listen to our bodies, we can take those initial cues of pain as a sign that something is amiss. Improving our movement patterns can prevent further deterioration, and will allow our knees to heal.

As we will see, a common problem occurs when martial artists don’t properly rotate their hip joints. This requires the knee to participate in excessive amounts of rotational movement. Over time, this leads to wear and tear, and results in knee pain. If we listen to our bodies, we can take those initial cues of pain as a sign that something is amiss. Improving our movement patterns can prevent further deterioration, and will allow our knees to heal.

While we are talking about anatomy, let’s take a moment to understand how our hip joints rotates. There are two ways that the femur can rotate within the hip socket (the acetabulum):

- Externally / toward the outside—laterally. Some arts call this “open hip,” since, in this position, the angle formed by hip crease / inguinal crease – the angle between the pelvis and the femur— is “wide open.” In Chinese arts in particular, the hip crease area is called Gua or Kua.

- Internally / toward the inside—medially. Some arts calls this “closed hip,” since, in this position, the angle formed by the hip crease is small or “closed.”

Now that we have an understanding of the anatomy, let’s talk about alignment and power generation.

Now that we have an understanding of the anatomy, let’s talk about alignment and power generation.

Power Generation Body Dynamics

Most martial artists use some variation of pelvic rotation to generate power. We are taught to use our entire body to strike, as opposed to punching or kicking with just our limbs. Here is an example from Gichin Funakoshi’s classic book Karate-Do Kyohan, The Master Text (originally published in 1921). In explaining the reverse punch (gyaku-tsuki) Master Funakoshi says:

“The attack is executed with the hips springing to a full frontal position form a half-facing (hanmai) position, with the cocked right fist being thrust forward in a movement synchronized with the hips.”

Another example is my friend and fellow karateka Noah Legel, performing a technique from Naihanchi Nidan kata. See how nicely he utilizes his hip to generate power.

This hip rotation movement is also common in boxing (boxers commonly pivot on their back leg, to maximize the rotation movement of the hip) as can be demonstrated below:

This hip rotation movement is also common in boxing (boxers commonly pivot on their back leg, to maximize the rotation movement of the hip) as can be demonstrated below:

The basic idea is that, for maximum power generation, we want to have the entire body moving toward the target. The limb is thought as a “delivery tool” for that power, and is not the main generator of power. For a detailed discussion of power generation, see this article.

The basic idea is that, for maximum power generation, we want to have the entire body moving toward the target. The limb is thought as a “delivery tool” for that power, and is not the main generator of power. For a detailed discussion of power generation, see this article.

As we take care of the health of our joints, a good place to start is by assessing how we use our knee, hips and feet in martial arts practice.

Trouble in Power Generation

Unfortunately, often times our ego gets the better of us. In an effort to “generate more power,” or hit a target that is out of range, we compromise our body alignment. Here is an example, from a karate kumite point match.

Take a look at the forward and back knees of the karateka. Do you think either of them can punch hard or absorb a punch in their current position? Of course not. They are over extended, and precariously balanced. (As an aside, jyu-kumite point matches, especially of the no-contact/ light-contact type, can accentuate bad form and mis-alignment. This is because this type of play rewards speed and range over hitting power and good structure.)

Misalignment is not isolated to sparring, here is an example of compromised position during pad drills. Take a look at the karateka’s collapsed back leg.

Optimal Knee Alignment

For optimal function, the knee joint should be kept be in straight alignment at all times. In other words, the knee must be in pointed in the same direction as the toes, with the hips, knee, ankle and foot in a single geometrical plane. We are looking to minimize any rotation at the knee, while maximizing the knee’s ability to flex, extend, and transfer forces.

Another aspect of good knee alignment relates to the health of our kneecap – the patellofemoral joint. When our knee is bent forward excessively, the loads on our patella (kneecap) and surrounding structures are heightened. A good rule of thumb is to make sure that, as you look down toward your own feet, you can always see your toes. If your view of your toes is obscured by your knee, this is a sign that your knee is excessively bent forward.

Let’s take a look at our front knee first. The photos below demonstrate proper and compromised front knee alignment. In the left panel, the front knee is properly aligned. The head of the femur is externally rotated in its socket, and the front kneecap is pointing in the same direction as front toes. From this position we can generate good power while maintaining a healthy movement pattern.

In the right panel, the front knee is compromised: the kneecap is pointing to the side, and knee is “collapsed” to the inside (medially). This position sometimes manifests in martial artists who misinterpret the cue “use your hips.” Instead of rotating at the hip joint, they over-cock their pelvis by twisting the knee.

In the right panel, the front knee is compromised: the kneecap is pointing to the side, and knee is “collapsed” to the inside (medially). This position sometimes manifests in martial artists who misinterpret the cue “use your hips.” Instead of rotating at the hip joint, they over-cock their pelvis by twisting the knee.

Now, let’s take a look at our back knee (the knee of the back leg in our stance). Again, the photos below demonstrate proper and compromised front knee alignment. Rear knee misalignment is a little more subtle to observe, although it has just as negative long term consequences as front knee misalignment.

In the left panel, the rear knee is properly aligned. The body weight is “sunk” into the rear hip/ gua, and the head of the femur is internally rotated in its socket. The rear kneecap is pointing in the same direction as the rear toes. This is an anatomically strong position for the rear knee. Additionally, from this position we can utilize the rear leg to power our hip and, consequently, our punch.

In the left panel, the rear knee is properly aligned. The body weight is “sunk” into the rear hip/ gua, and the head of the femur is internally rotated in its socket. The rear kneecap is pointing in the same direction as the rear toes. This is an anatomically strong position for the rear knee. Additionally, from this position we can utilize the rear leg to power our hip and, consequently, our punch.

In the right panel, on the other hand, the rear knee is compromised. Take a close look and you will see that the kneecap is pointing to the side, and that the knee is “torqued” to the outside/laterally. As with the front knee, the reason is that the martial artists attempted to over-rotate their pelvis in the belief that “more is better.” Instead of rotating internally/ sinking into the rear hip joint, they are achieving pelvic rotation by twisting the knee toward the back. It is also likely that the rear foot supinated, that is, the toe of the back foot is “light,” and weight is felt more heavily on the edge of the back foot.

Note that alignment is a dynamic concept. The knees should be in good alignment not just at the end points of a movement, but also throughout the movement. For example, imagine yourself standing in a front stance (as in karate’s zenkutsu-dachi, or kung fu’s bow-and-arrow stance), and throwing alternating punches. Your knees should remain in good alignment throughout the entire movement and not just at the end points. Here is an example of improper dynamic alignment of the rear knee. Observe how it is collapsing toward the inside during the reverse punch.

Identifying Knee Alignment Issues

As with any other issue, identifying the problem is the essential first step toward a solution. There are several good ways to check your static and dynamic knee alignment. Those include:

- Observing yourself in a mirror while performing martial arts techniques, shadow boxing, working on a heavy-bag or makiwara, or practicing kata.

- Having an instructor or a fellow student observe you. The benefit of this approach is that it can also be applied successfully to non-cooperative play and sparring, where self-observation is much more difficult.

The goal here is to improve our alignment and technique by sharpening our proprioception. Proprioception is our ability to grasp the relative position and effort exerted by the different parts of our own body. In additional to visual cues (us, or our coach, observing our alignment), tactile cues can be very helpful here. I am specifically referring to the feeling in our feet.

Our feet have many proprioceptive nerve ending, and our bodies constantly rely on the “sensors” in our feet to aid in our balance and gait. Proper knee alignment can be felt in our feet. When our knee is in proper rotational alignment, our foot will feel that it carries weight evenly. Conversely, when our knee is out of alignment (over-rotated to one side or another), our foot will have a feeling of being rolled to one side. The foot will usually also be pronated if the knee is misaligned to the inside/medially, and supinated if the knee is misaligned to the outside/laterally. For simplicity, it is helpful think of pronation as the foot being rolled to the inside, and of supination as the foot being rolled to the outside.

Fixing Knee Alignment Issues

There can be many reasons for our knees to be are out of ideal alignment as we practice martial arts. Generally speaking, those reasons fall into three categories:

- Insufficient range of motion in neighboring joints– usually, in the hip, ankle, or foot. Our body is a champion at trying its best to do what we ask it to do. If there is insufficient range of motion in one joint, the body will try to compensate by over-mobilizing another joint.

- Weak musculature in our core: legs, hips, abdomen and/or back. There are many muscles whose role is to stabilize the body. A deficiency in strength in any of these muscles, e.g., because of a job that has us sit for many hours each day, will make it difficult for us to maintain good posture and alignment. Again, our body will do its best to compensate for the deficiency by recruiting the knee.

- Incorrect movement patterns. In other words, we have not learned, or sufficiently ingrained good and healthy patterns of movement.

You will do well to seek professional advice for range of motion and muscular deficiency issues. A good physical therapist (and some of the more talented personal trainers) can help diagnose and resolve those. I will therefore move to discuss movement patterns under the assumption that there are no underlying physiological issues that prevent you from moving properly.

Many martial arts instructors emphasize the use of hip rotation to generate power. Students have probably heard the advice “move from your hips,” and “turn your hips more.” That is all fine and good. However, it can lead some students to misunderstand power generation and gamaku as over-rotation of torso.

Hip and torso rotation is not a case of “more is better.” The hips joint has the most variation between different individuals. Simply stated, some of us have the anatomy that allows our hip to rotate a lot, and others do not.

Beginners often focus on what is happening at the limb that is “doing” the techniques. This can often lead to “over-extension,” of hips and torso, in a failed attempt to generate more power. Over-emphasizing the rotation of the hips and torso will lead our body to “cheat” by recruiting other joints (usually, the knee and the spine). This compromises our postural alignment, robs power from our technique, and also makes us prone to injury. Experienced martial artists know that the key to generating power lies in maintaining correct alignment through movement, and within our body’s natural range of motion.

Personally, instead of trying to “jerk” the pelvis in an attempt to generate power, I prefer to think of the hips as one part of our power-generation kinetic chain. As the Tai Chi Classics tell us:

“The [power] should be rooted in the feet, generated from the legs, controlled by the waist, and manifested through the fingers.”

The key is to think about moving the torso and the pelvis by “opening” and “closing” the hips. That is, by rotating the head of the femurs, externally or internally, inside their socket. This movement should be done within whatever range of motion our own hip affords us. It does not need to be large.

An Example and Suggested Drill from Naihanchi Kata

Naihanchi kata is a cornerstone katas in several Okinawan karate styles. It is an excellent tool in teaching us how to generate power. As we perform the kata, we are facing forward, while executing both frontal and side techniques. We learn how to use our entire body to generate power in those techniques by “sinking” into one hip or another.

Knee misalignment in Naihanchi kata will usually manifest as excessive side-to-side movement of the knee. It is easy to diagnose by doing the kata in front of a mirror. The exercise below uses a band to help teach us improved knee alignment in Naihanchi kata:

Progressive Training Plan

Increased psychological stress will usually lead to deterioration of technique. Initially, we may be able to maintain good body dynamics during standing basics, but our techniques will deteriorate as we try to hit a target, and it will deteriorate even further when we spar.

A good progressive plan is as follows:

- Start by noting and fixing your joint alignment while doing static basic moves – punches, blocks and kicks from a standing position. Work on different stances.

- Once you have mastered alignment in static poses, add movement – moving basics and shadow boxing. If you note loss of alignment in a move, practice that move again, and get to the root cause of the disruption.

- Move on to doing kata (forms) while maintaining good joint alignment. The variety of movements and transitions in kata will help your body’s “muscle memory” learn the intuitive position for your joints.

- Incorporate impact drill, on both static targets such as a heavy bag or a makiwara, as well as on dynamics targets in different pad drills. If you note loss of joint alignment, dial back the power and focus on fixing the root cause. Power will come with good alignment and with time.

- Test things in sparring and other non-cooperative drills. It is natural that when both partners are moving, things become chaotic. While you will not be able to execute every move with perfection, your aim is that joint alignment will be maintained at all times or, as close as possible to all times.

In Summary

In conclusion, knee pain is unfortunately a common affliction of martial artists. By maintaining good knee alignment, we can not only increase power in our techniques but also maintain the health of our knees for year to come.

Excellent article and advice on knee issues!

Thanks!

My experience in treating knee issues in martial artists goes back 4 decades, and I must tell you that by the time they have constant pain in the knee, there is often overuse damage. Sometimes this damage can be so extreme that some cannot be fixed. Your point about alignment of the knee is right on and this should be corrected early if possible, not after degenerative changes are present.

Jim:

I absolutely agree! It’s best to fix knee alignment issues early, and the point of this article is to raise awareness for this topic.

In visiting different karate dojos around the world I have ran into many places that simply don’t emphasize good alignment. I have also seen many senior students (and, dare I say, instructors) who have less than optimal joint alignment.

The beauty is that investing time in improving one’s karate bio-dynamics is worthwhile in more than one way. Improved bio-dynamics reduce injury risk, and also increase power.

Brian

Should have read this a long while ago. Could have avoided permanently damaging my knee.

Great article. Well worth the read.

Much of what is written here resonates with the form we try to instill in our karate students.

I have a prosthetic left knee and constant right knee pain from overcompensating for the left. I’ve been working with the band for about a month now and while there is still some pain, it is greatly improved, as is the tone of the muscles in both legs.

Thanks!

Hi Noah!

You are most welcome.

I am glad the article and exercises helped your knee!

Brian

I’ve just started with right knee pain This article is awesome. Thans so much!!

You are welcome!

Unfortunately, there is quite a bit of karate knowledge that got misinterpreted over the years. This results in unhealthy ways of practice.

Take care of your body! Healthy movement that respects how our bodies were designed to move is not just better for you — it is also more powerful!